Lens-Artists Photo Challenge #348 | Serenity

Lens-Artists Photo Challenge #348 | Serenity

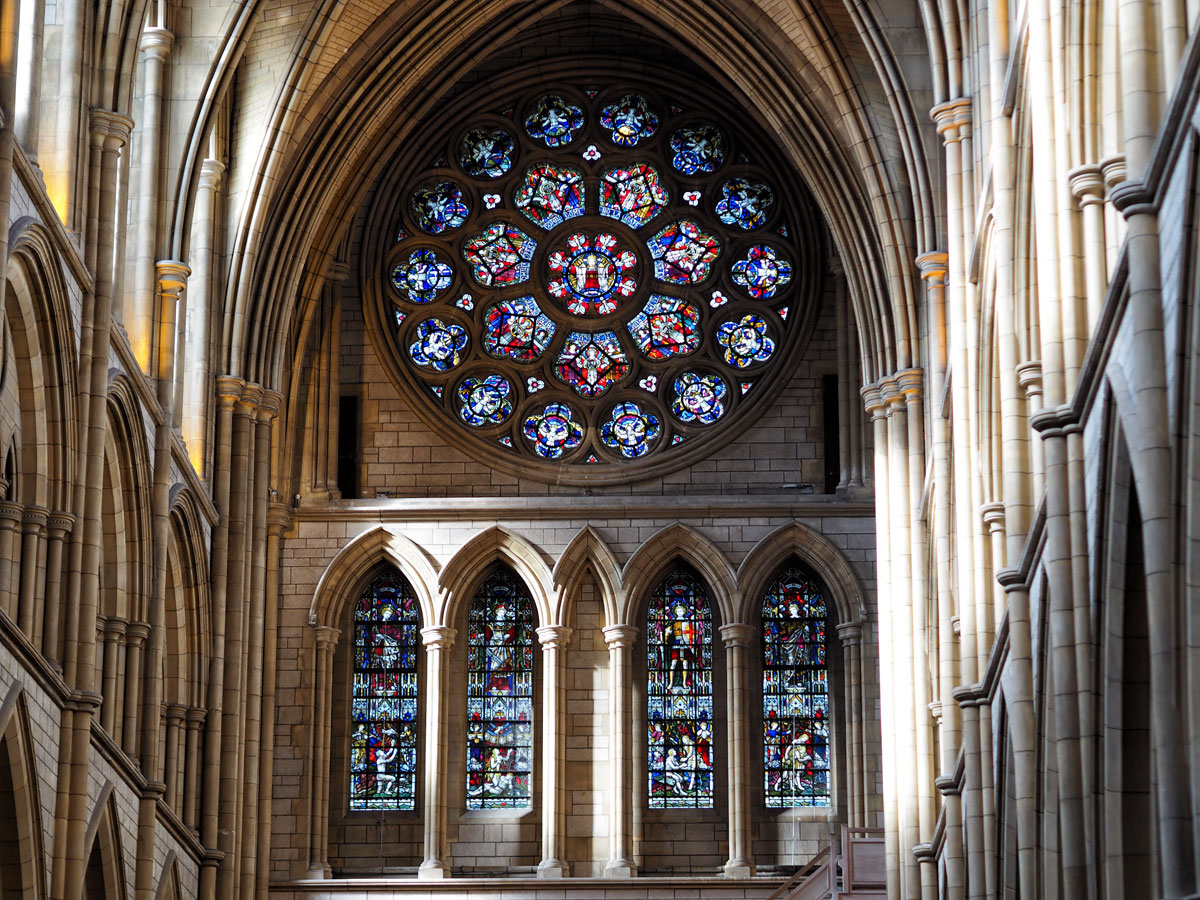

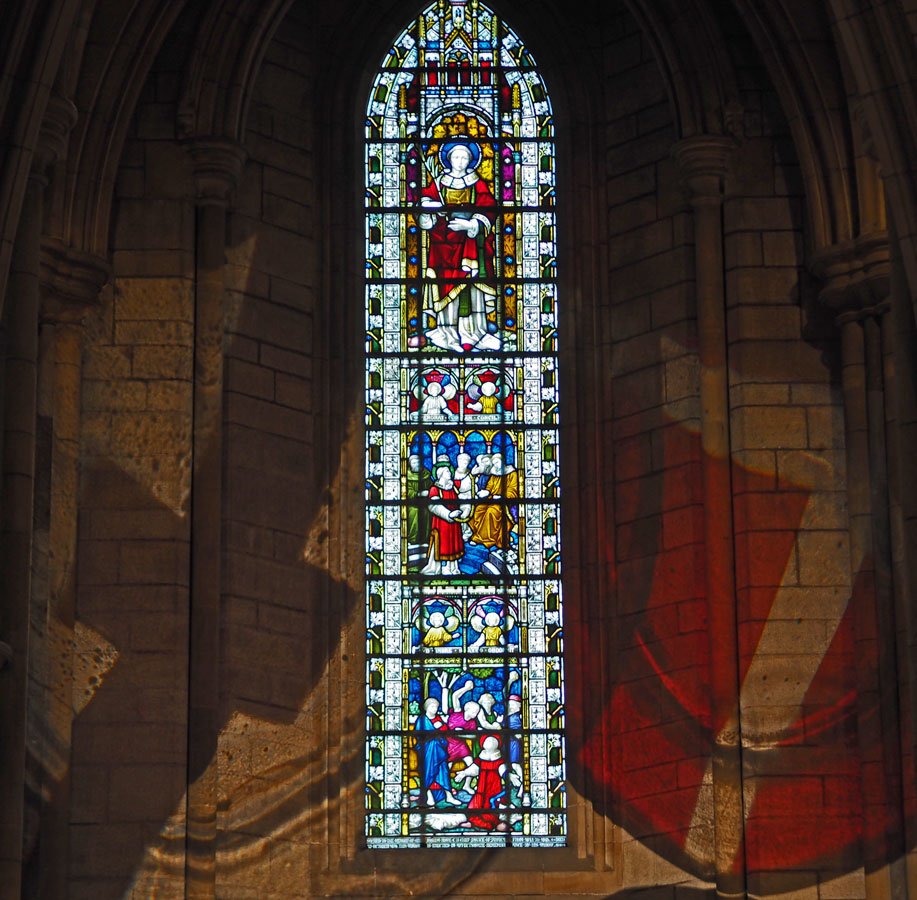

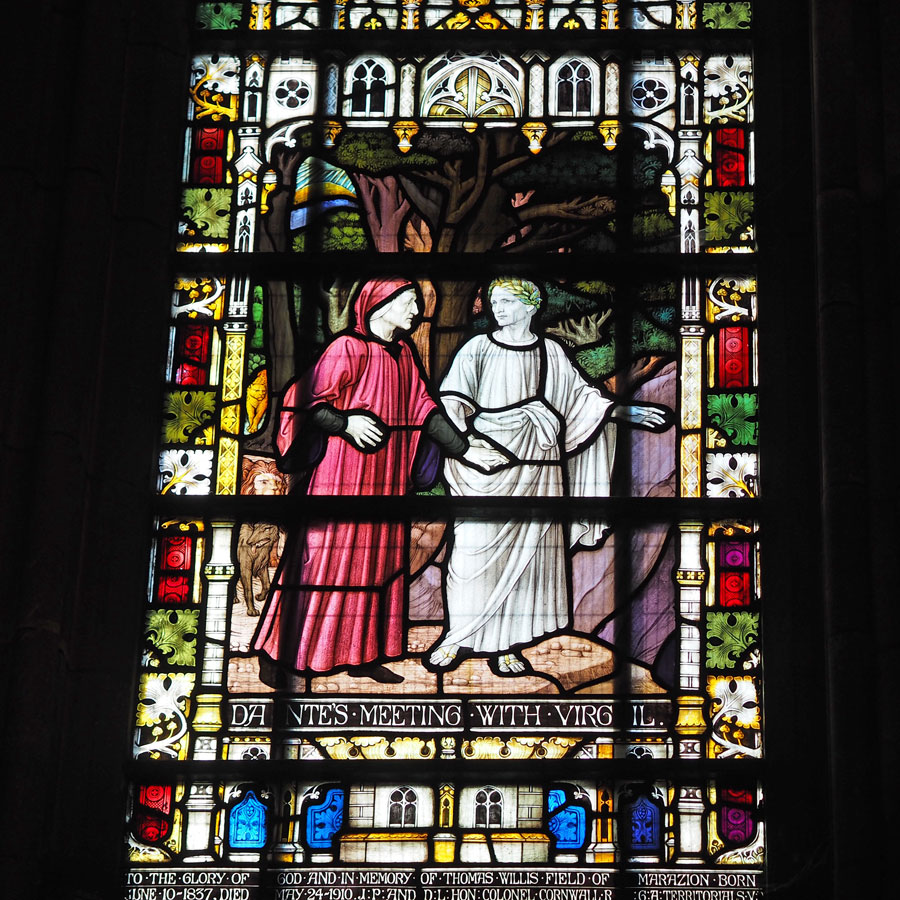

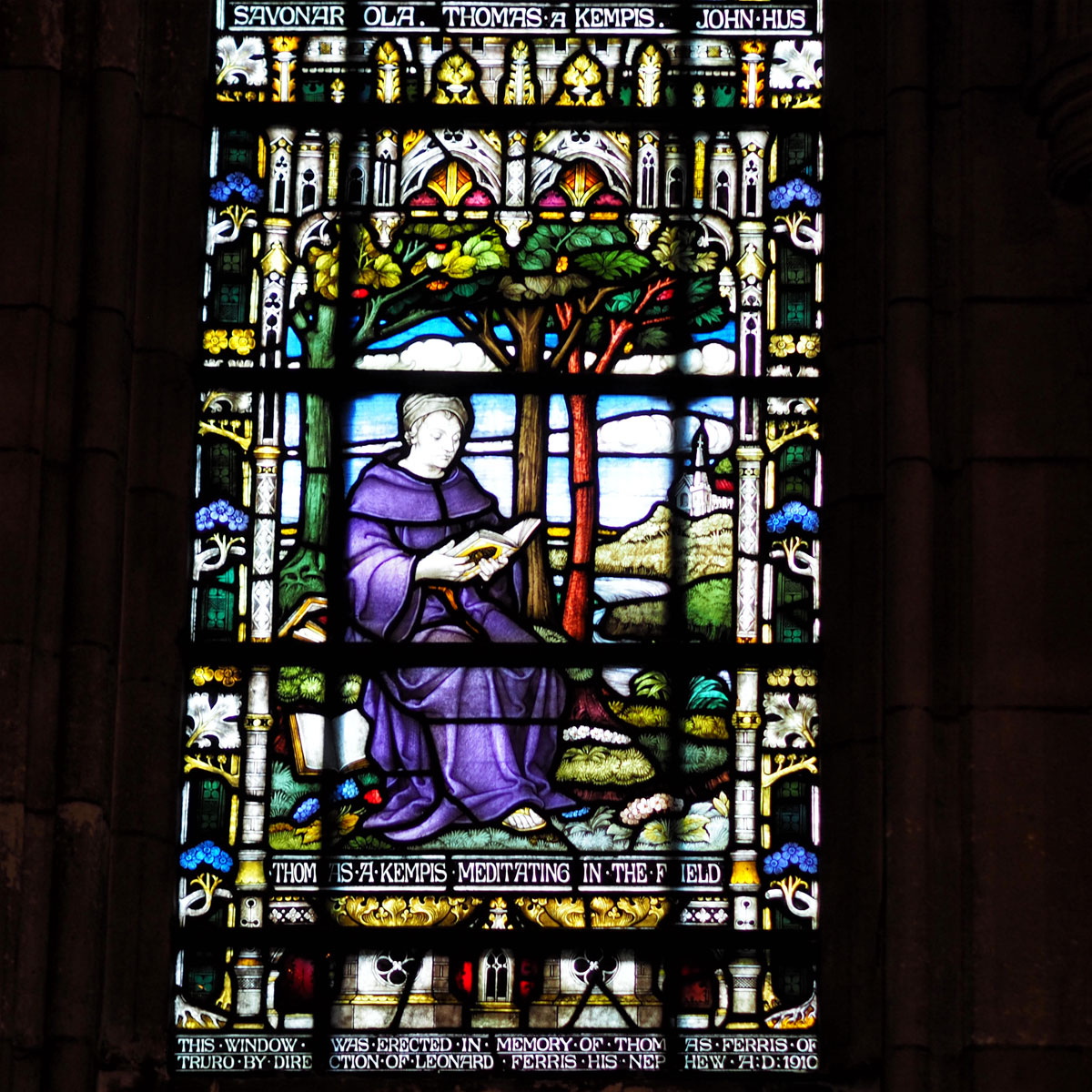

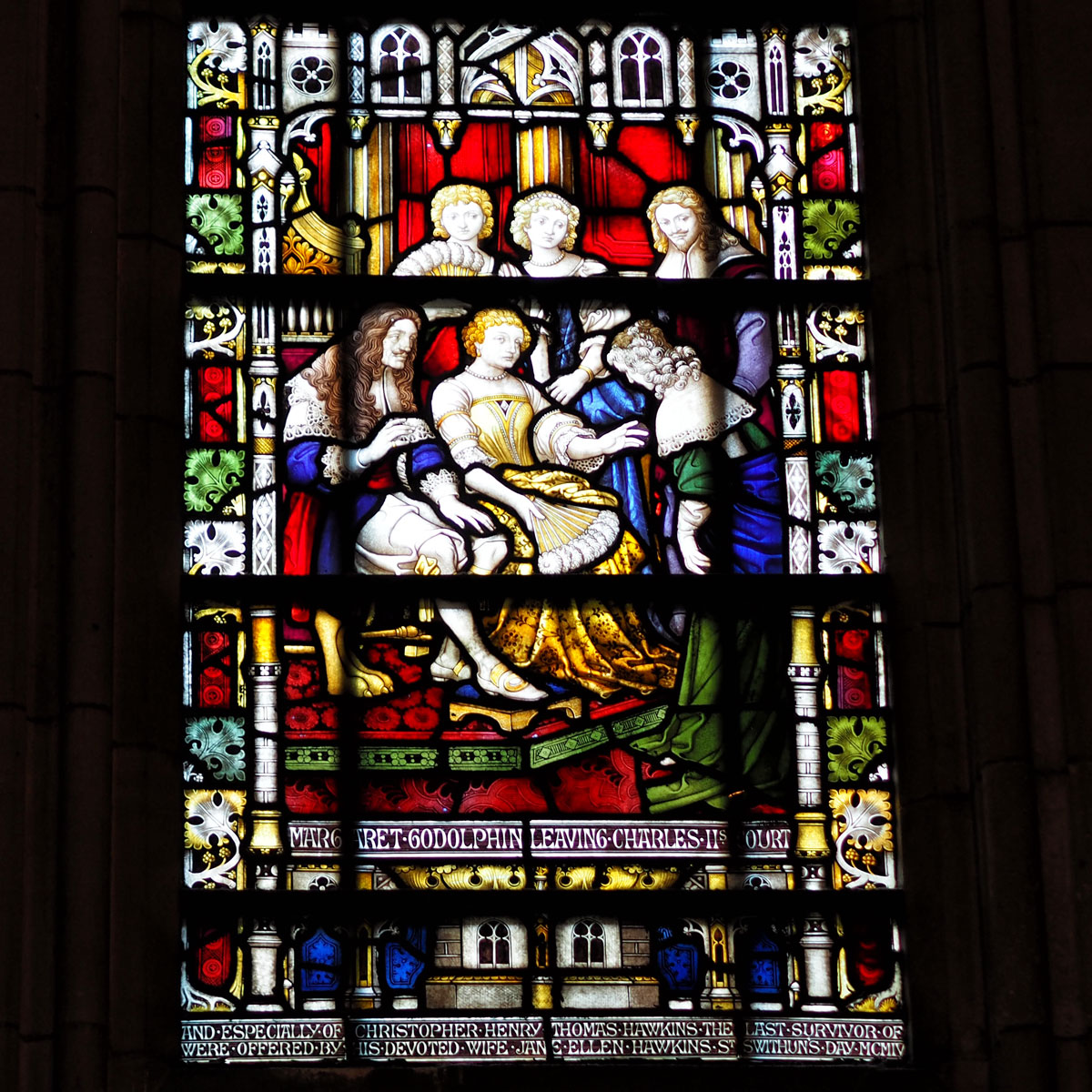

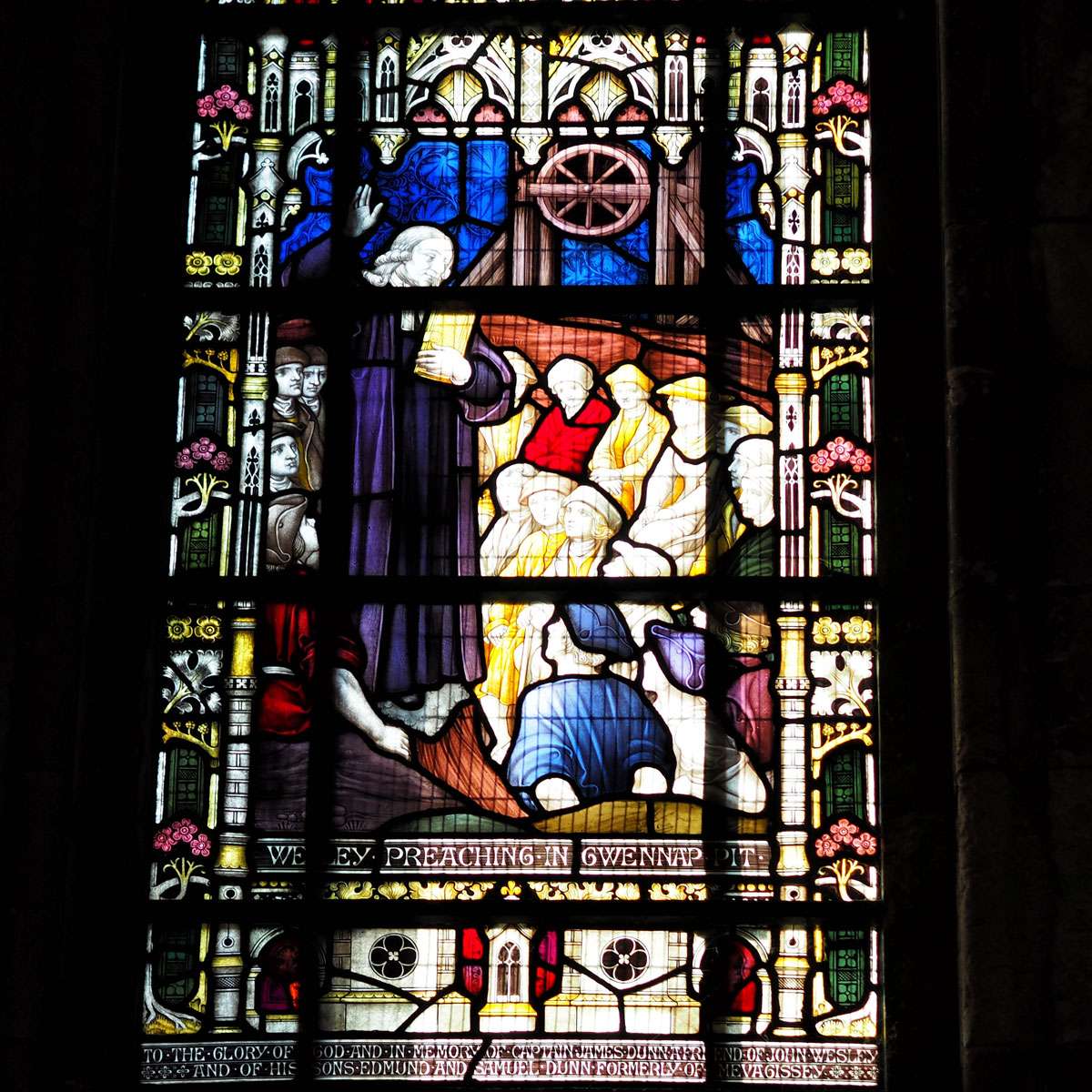

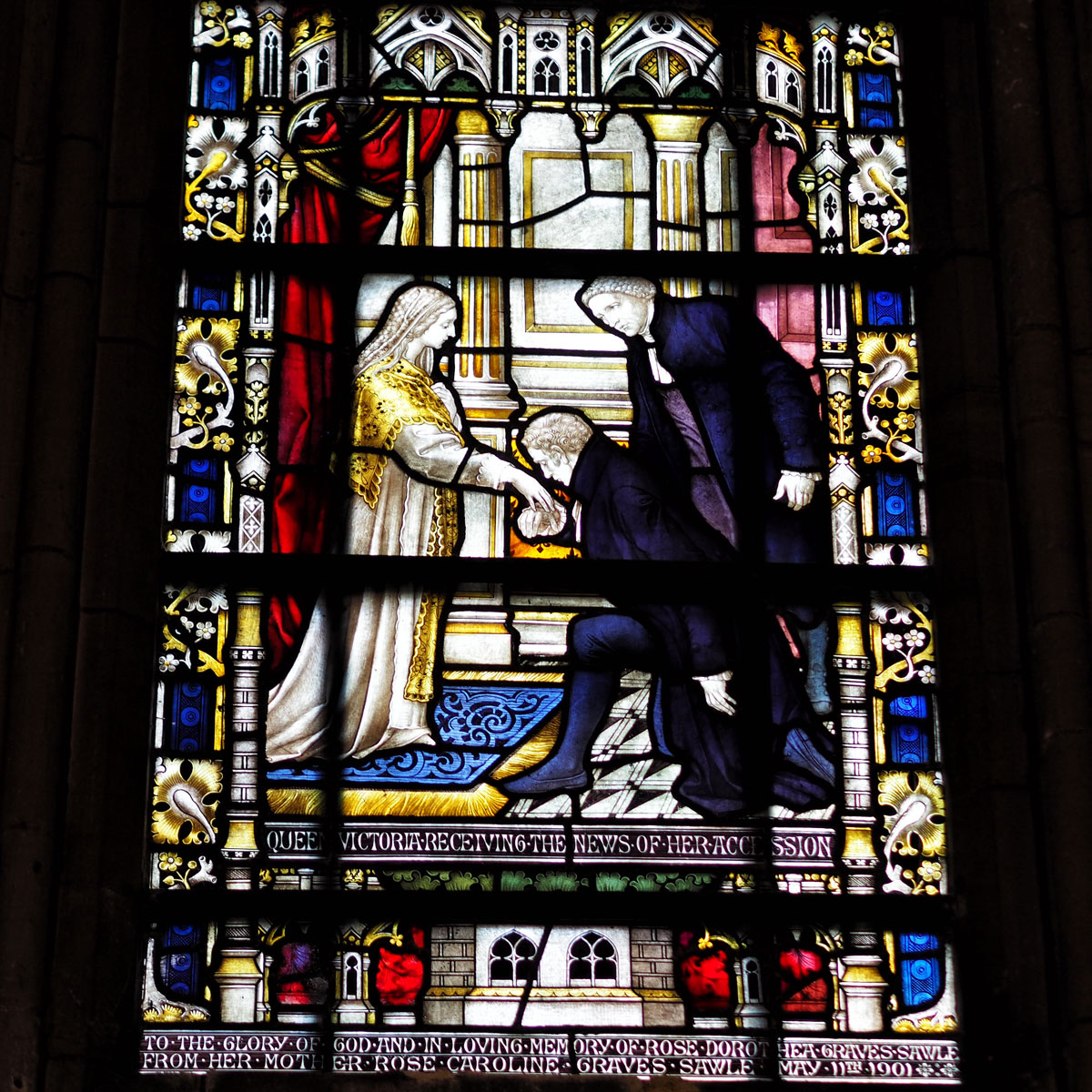

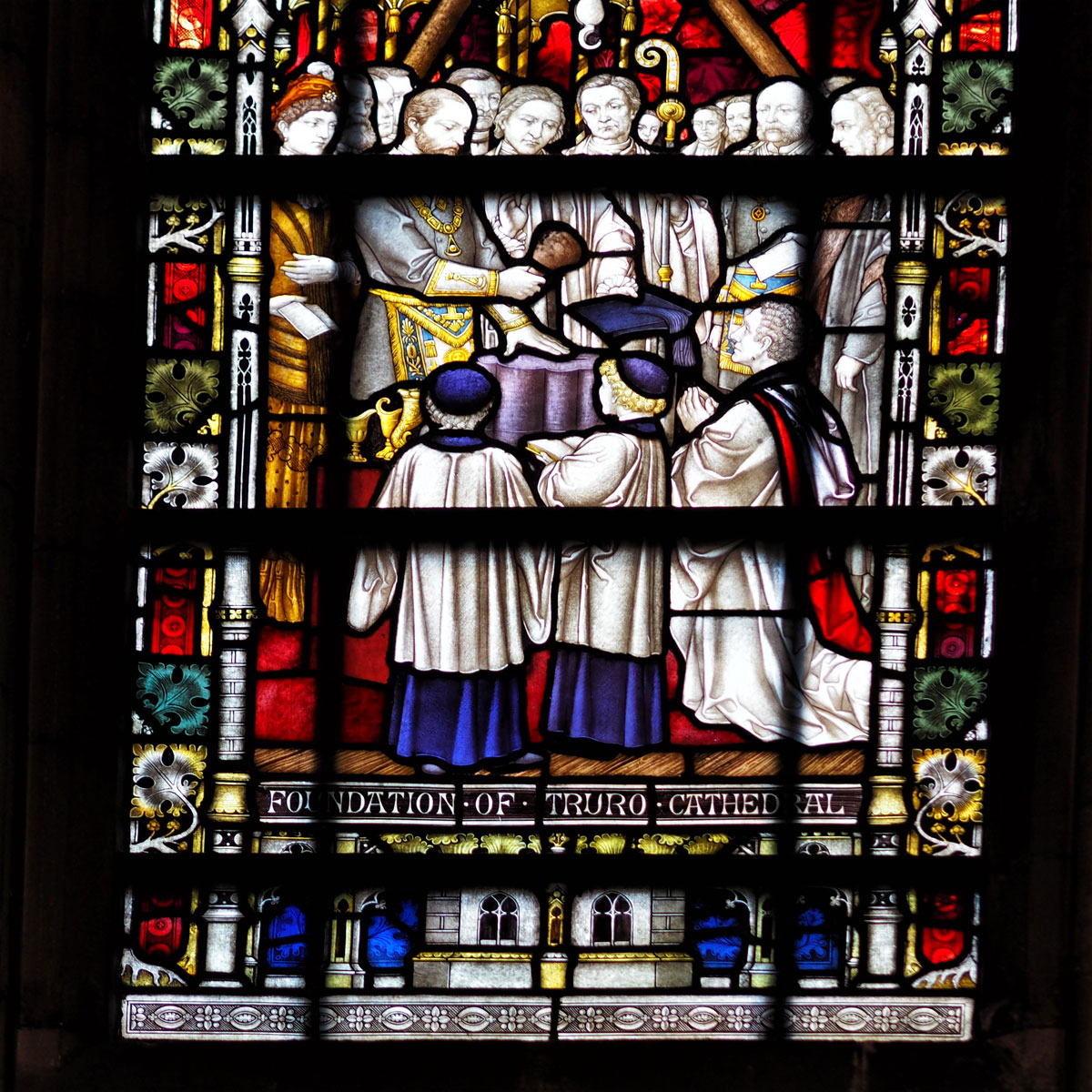

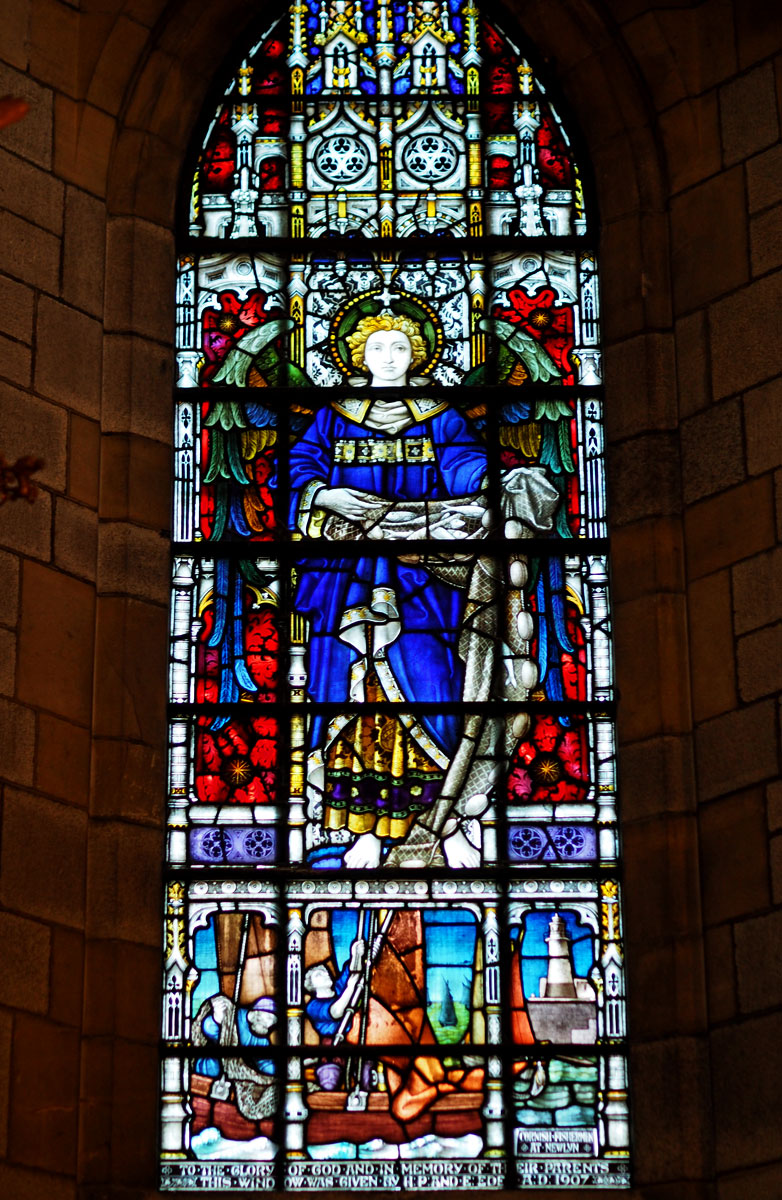

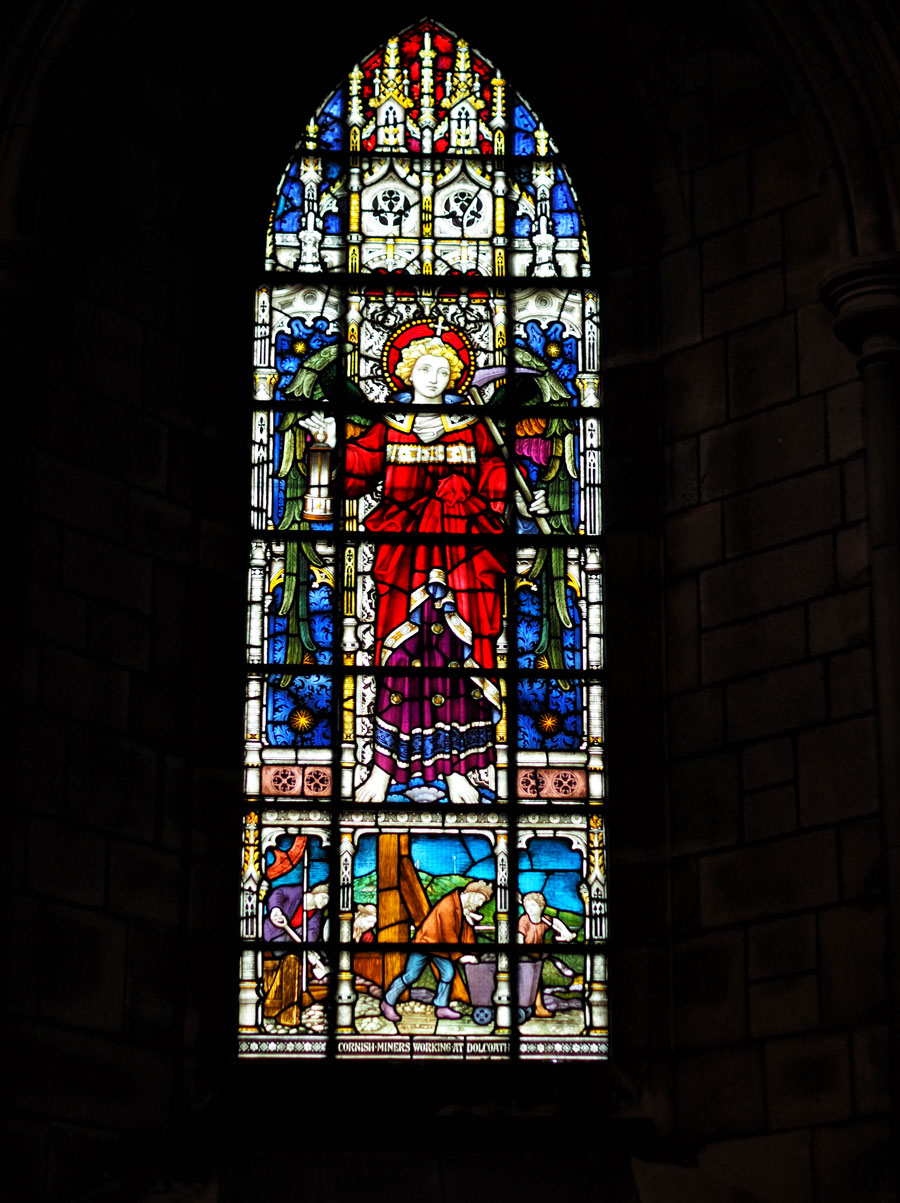

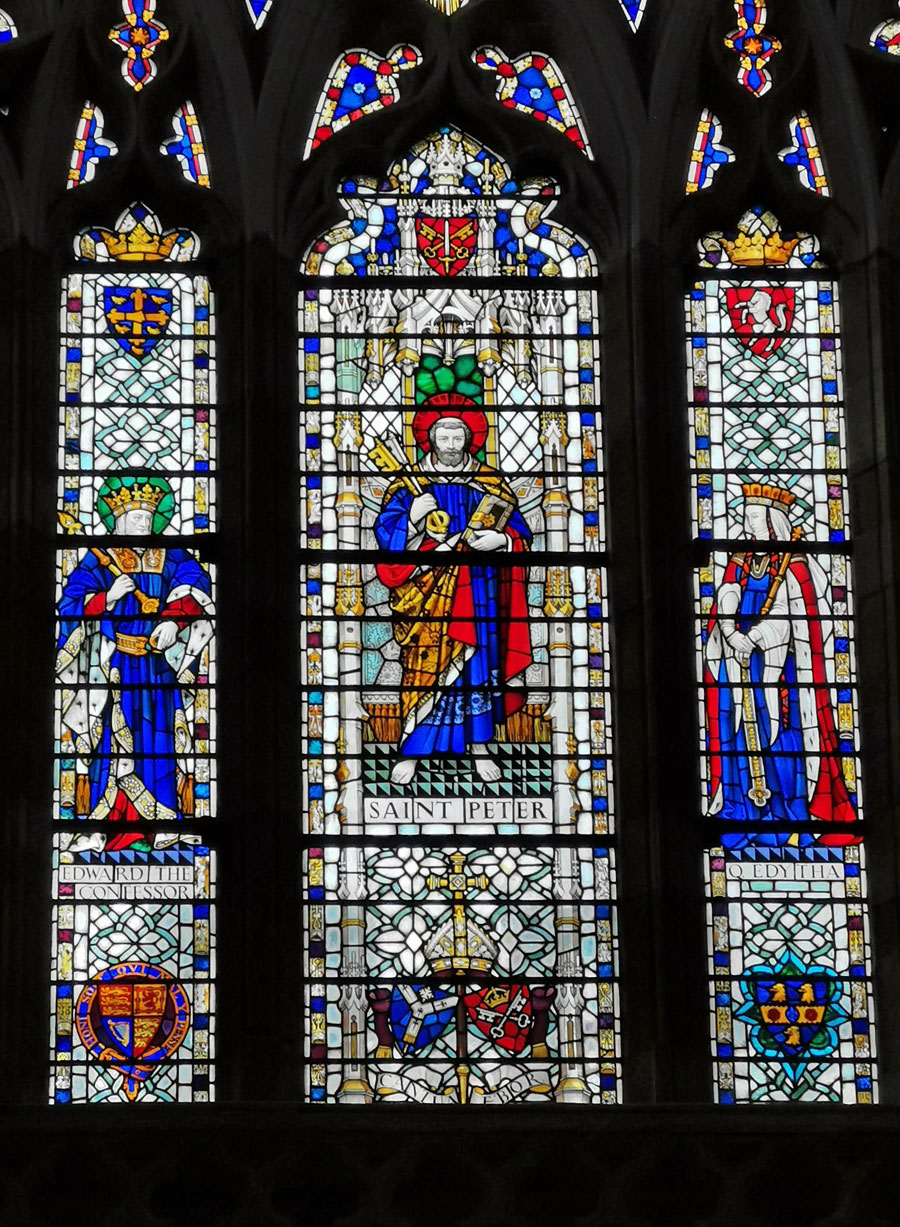

It was the largest stained glass project ever executed and has some of the finest Victorian stained glass in the country, produced by the leading company of the time: Clayton and Bell. The scheme has three big themes: the Trinity, Biblical stories and the history of the English church. Alongside these are three lesser themes: Cornwall, baptism and St Mary’s aisle.

There is a recommended route, so that the interrelationships between the windows in each part of the Scheme can be explored, but of course I hadn’t realised that. Now that I do it may be a good reason to return to the cathedral and be more observant.

The greatest windows are the three great rose windows which reflect the Trinity;

God the Father/Creator appears in the great West window which is divided into seven sections for the seven days of creation

Jesus, the Son of God, is at the heart of the North transept rose surrounded by the prophets and his antecedents: Jacob, Isaac, Judah and Abraham, leading through to Mary and Joseph.

The Holy Spirit is at the centre of the South window with the twelve apostles around the edge.

The biblical stories are told in and around the quire. The great east windows tell the story of Christ and his Passion.

The Deposition. The angels at the top hold the Crown of Thorns and the nails with which Jesus was fixed to the Cross

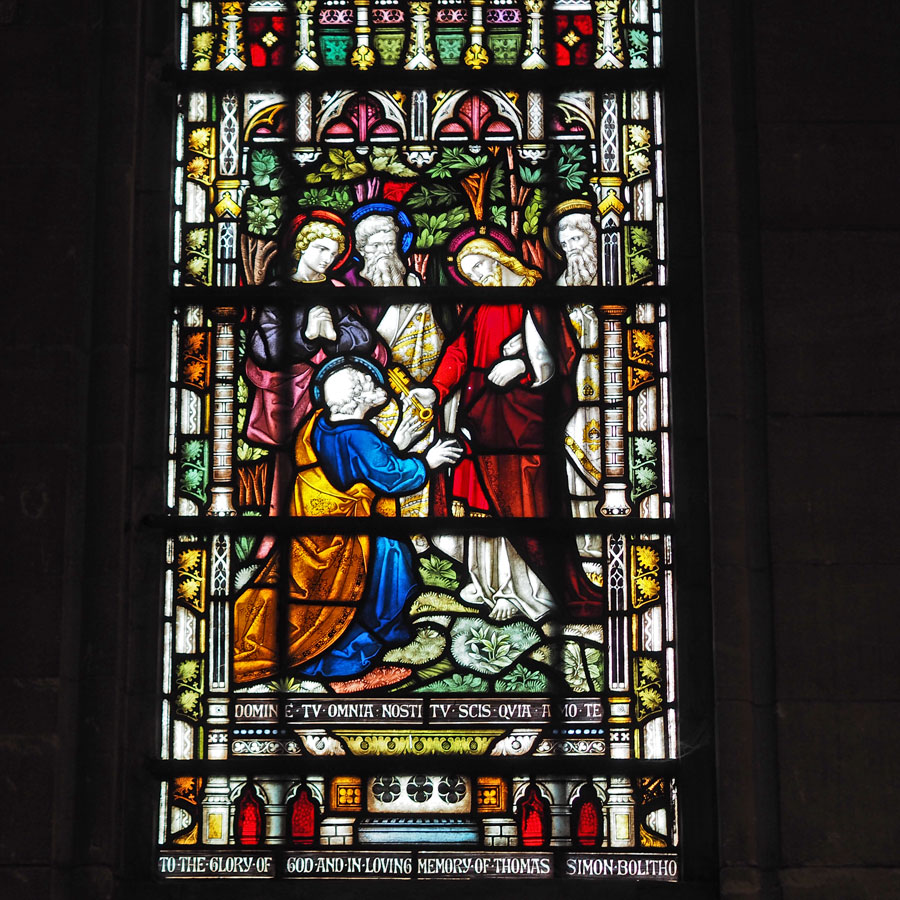

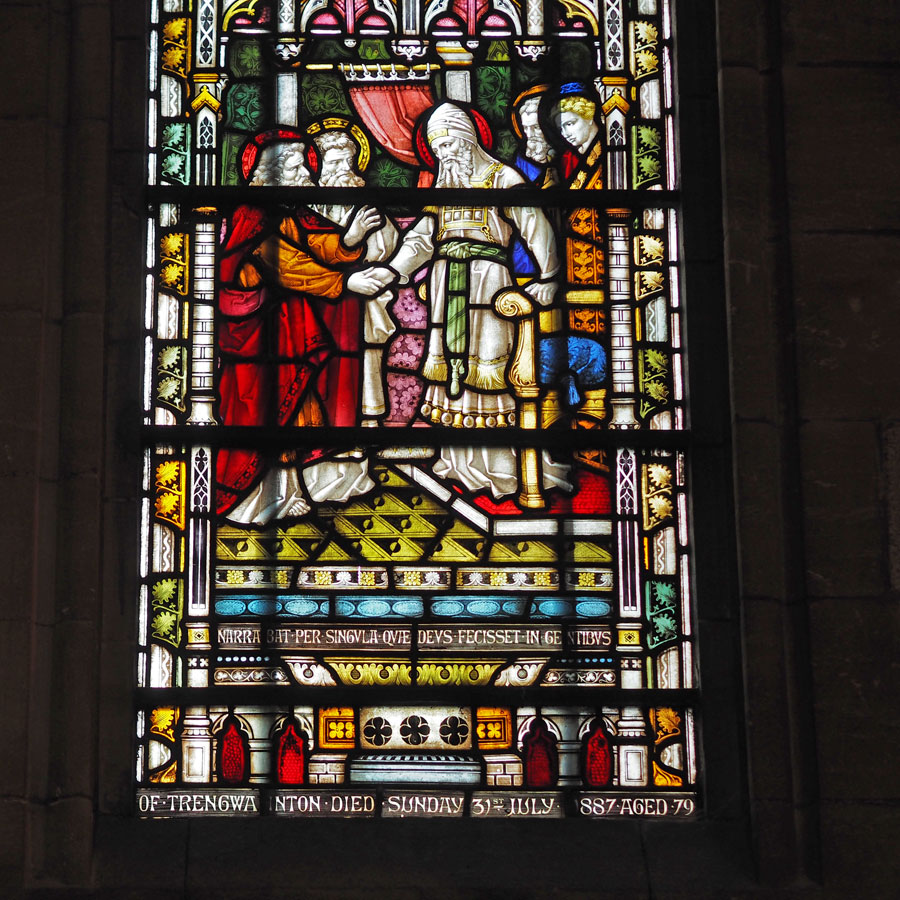

The choices reflect the late Victorian sensibilities and the enthusiasms of the two creators, like, for instance, the execution of King Charles I which I didn’t see. There is a flow to the sequence that does make sense. The theme starts in the South transept through to the retro-quire and quire. This section begins with St Peter receiving the keys from Christ and ends with St Benedict though my photos are rather more random.

In the foreground are eight boys kneeling and looking at Colet. The scene refers to the end of the preface to the Latin grammar that he wrote for the school: “And lift up your little white hands for me, which prayest for you to God … ” There is a picture of the Child Jesus in the background. In the rear at the High Master’s desk is the celebrated scholar William Lily, the first High Master of the school.

Margaret Godolphin, née Blagge, of Godolphin House between Helston and Penzance was a Lady in Waiting to the Queen at the court of Charles . She was a vigorous opponent of the lax moral tone of the court and resigned her position there in protest. She died in and is buried in Breage Church near Helston.

He is dressed in Masonic regalia and holds a maul. He is surrounded by a number of other figures associated with the occasion and the Cathedral, including the Princess of Wales, John Loughborough Pearson (Architect), Prince George and Prince Albert Victor. The background features scaffolding and other evidence of building work.

Cornwall’s industry is included in the west nave windows, which feature mining and fishing through images of miners, fishermen, Newlyn harbour and Dolcoath mine.

And finally, there are the windows in St Mary’s aisle, which has some mid-Victorian windows from the original St Mary’s church on traditional biblical subjects, as well as some medieval fragments.

Each light shows a main figure above a related scene, and all are connected by the imagery and symbolism of water. This was, and still is, the baptistry area for the old parish church.

The six south wall windows are all by William Warrington. They are typical examples of his use of bold primary colours, strong leading, dramatic design, and heavy painted shading.

It’s obvious that I need to return!

It’s been a long while since I was last in Truro (other than hospital visits) and I never did get around to writing about the cathedral. On my first visit I wasn’t very enthusiastic, but my second was better and I was more interested in looking around. At the time there was some kind of exhibition which was very attractive and which has reminded me that maybe I should make another trip to the city and cathedral.

Formerly the site of St Mary’s Church, the Cornish Diocese of Truro was formed in 1867 and St Mary’s became the cathedral church. In 1880 the Foundation Stones of the cathedral were laid by Edward, the Prince of Wales, Duke of Cornwall. Work started on the cathedral under John Loughborough Pearson. Truro would be the first Anglican cathedral to be built on a new site since Salisbury Cathedral in 1220.

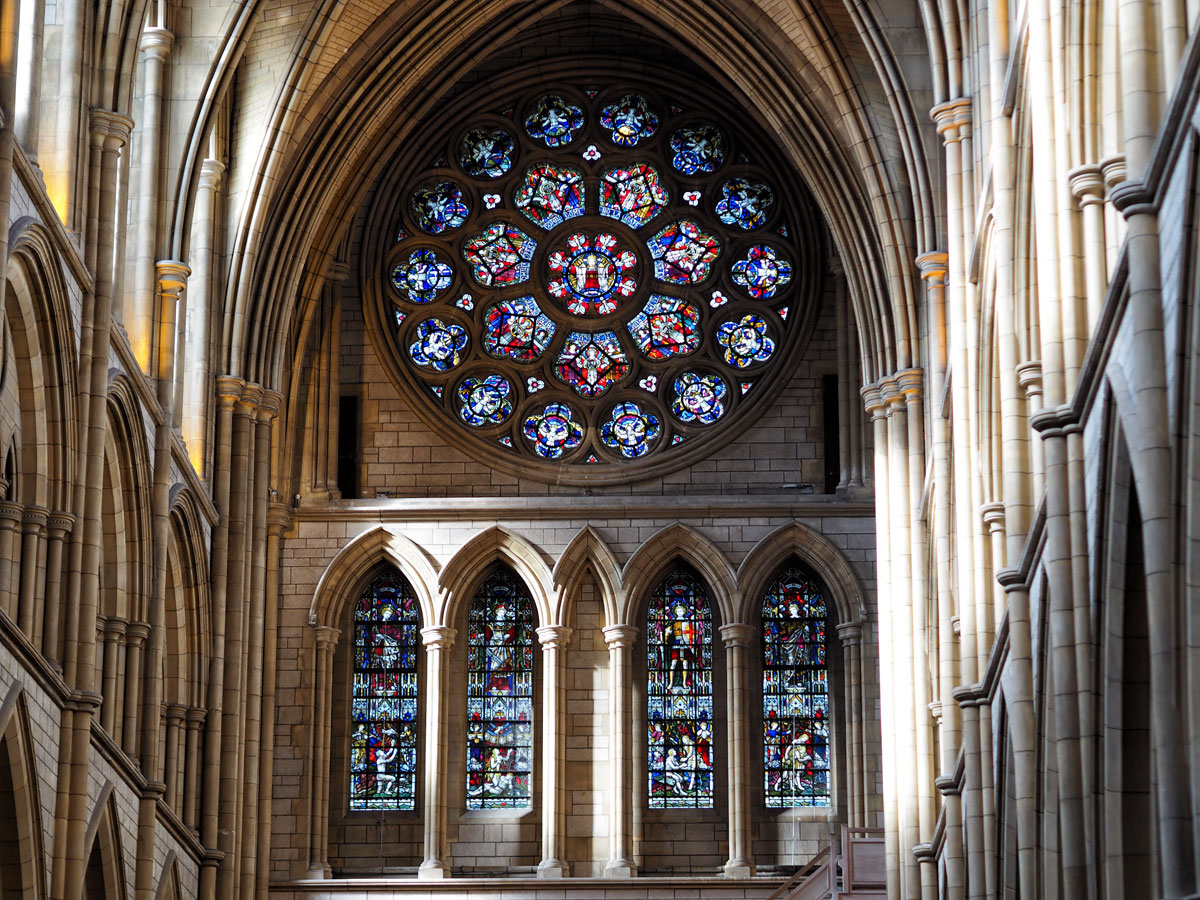

The architecture of the cathedral is often likened to that of Lincoln cathedral and French cathedrals like that at Caen: a mixture of Early English (Lincoln and Salisbury) and French Gothic. While the three simple spires are reminiscent of a French cathedral, Truro is only one of four cathedrals in the UK with three spires.

The light inside was wonderful on this day.

Truro cathedral has three beautiful circular rose windows, part of the large and inspiring collection of Victorian stained glass created by Clayton and Bell.

God the Father: Truro’s west rose is the first of the sequence of three rose windows on the theme of the Holy Trinity. It is divided into the irregular number of seven inner and fourteen outer sections: this is to accommodate seven angels holding shields signifying each of the six days of creation and the seventh Day of Rest in the inner ring.

The statues of Bishops and saints are tinted, standing out amongst a sea of intricate wooden carvings. No misericords, unfortunately, nor are there any tombs in the floor of this Cathedral, far too young.

As usual, I wander around looking for quirky details, reflections, light, shadow, colours that appeal to me.

The Tinworth terracotta panel at Truro Cathedral is extraordinary. “Our Lord on His Way to Crucifixion” made by George Tinworth, master craftsman and chief designer at the Doulton company is one of only three surviving examples of his large-scale religious works and the only one still on public view.

I’ll be back next week with a look at a few of the stained glass windows that caught my eye.

Exeter Cathedral was founded in 1050 with the enthronement of the first Bishop of Exeter and construction began in 1114, initially in the Norman (Romansque) style. The two towers are from this period. A major rebuild was done between 1270 and 1350.

Although it is 18 months since my visit to this cathedral I didn’t get around to posting about it. You may wonder why someone who is nonreligious enjoys visiting churches and other religious buildings. I can’t help admiring the craftsmanship that goes into these religious buildings. And of course they are a big part of our history.

White and honey stone was used to face the building, brought from quarries along the East Devon coast. Above the rows of statues is the beautiful 14th century tracery of the great west window and high up in a niche at the top of the west front is a modern statue of St Peter, the patron saint of the cathedral, depicted as a naked fisherman

Let’s head inside.

Measuring approx. 96m in length, Exeter Cathedral’s ceiling is the longest continuous medieval stone vault in the world. This style of vaulting is known as tierceron. The round stones (bosses) of the vault act as keystones and there are more than 400 of them carved with a variety of Gothic images including plants, animals, heads, figures and coats of arms.

One of the bosses shows the murder of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury by King Henry II’s knights. It is a rare survival as Henry VIII proclaimed in 1538 that all images of Becket were to be destroyed. Unfortunately I didn’t manage to photograph that one.

Overlooking the nave is this unique 14th century Minstrels’ Gallery. The purpose of it is uncertain; its name derives from the 12 angels along the front, all playing medieval musical instruments including the cittern, bagpipe, hautboy, crwth, harp, trumpet, organ, guitar, tambourine and cymbals.

As is the norm in any cathedral you will find a number of tombs.

Stories of Christian martyrdom through the ages are depicted in the stone panels of the 19th century Martyrs’ Pulpit. Designed 1876-7 by George Gilbert Scott, it shows the martyrdoms of St Alban, St Boniface and the Victorian missionary bishop, John Coleridge Patteson.

The Quire stalls were installed by Sir George Gilbert Scott in 1876 during a 19th century restoration of the cathedral. It is uncertain when the medieval choir stalls were removed, but the seats in the back row incorporate one of the oldest sets of misericords. Unfortunately they are not in good condition and only one is on display.

The Elephant Misericord is the most famous of a complete set surviving from the 13th century under the Prebendaries’ stalls. The carving may have been done from a drawing of the animal given as a present to Henry III

The clock in the north tower is an early attempt to represent the relationship of the earth, moon and sun.

A hole at the bottom of the tower door in the north transept of Exeter Cathedral for the Cathedral Cat. The cat kept down the population of rats and mice and had a recognised position as a member of staff, with salary of 13d a quarter or 4s. 4d. a year. (s = shillling and d = penny)

Also in the Nave is a memorial to the Polish 307 Squadron night-fighters who fought the Luftwaffe over the skies in Britain. On 15th November 1942 they helped protect Exeter from potential destruction. It was dedicated on the 15th November 2017, the 75th anniversary of the day that the squadron presented the city with the Polish flag as a sign of international co-operation.

Outside the cathedral, situated on the Exeter Cathedral Green, a statue of Richard Hooker dates from 1907 and is sculpted from white Pentilicon marble from Greece. Born in Heavitree in 1554, Hooker became an Anglican priest and influential theologian. Hooker was exceptional in promoting religious tolerance.

If the world should lose her qualities. If the celestial spheres should forget their wonted motions. If nature should intermit her course and leave altogether the observations of her own laws. If the moon should wander from her beaten way, the times and seasons blend themselves by disordered and confused mixture, what shall become of man who sees not plainly that obedience unto the law of nature is the stay of the whole world?

The quotation, from Hooker’s masterwork, Of The Laws of Ecclesiastical Politie

We didn’t spend a lot of time in Salisbury in June, because I was struggling with a ‘broken’ foot (my daughter insisted it was, but I thought possibly just torn ligaments – whatever, it was painful to walk on even after a month!). Apparently Salisbury has the largest Cathedral Close in Britain. It is a wonderful green space to escape the busy streets of Salisbury and to just explore and relax, with 21 Grade I listed buildings surrounding the magnificent cathedral, as well as museums and gardens.

Built between 1327 and 1342 the High Street gate is the main point of entry into the Cathedral Close. It housed the small lock-up jail for those convicted of misdeeds within the Liberty of the Close. Beside the gate stands the Porters Lodge.

One of five gates in Salisbury’s ancient city wall and one of the four original gates, the High Street Gate (see below) joins St Ann’s Gate, the Queen’s Gate, and St Nicholas’s Gate. On the town side of the gate is the Stuart royal coat of arms which was added in the 17th century.

There are several buildings in the Close which are open to the public; others you can only stand and peer through the wrought iron railings and admire their moss covered gabled roofs, mullioned windows and beautiful gardens. It’s a shame that the cars spoil the views.

These buildings mostly stem from the 18th century, when Salisbury was a place of refinement, learning and culture, and the wealthy moved to the area and built their fine houses. A mixture of architectural styles and designs, narrow alleyways that lead off to mysterious places and grassy lawns dotted with benches.

Arundells: Originally a 13th century canonry built around 1291, the last canon who lived here, Leonard Bilson, was imprisoned for practising magic and sorcery in 1562. The frontage is Georgian, the work of John Wyndham who lived there from 1718 – 1750. The house got the name of Arundells after James Arundell, the son of Lord Arundell who lived there from 1752 – 1803. Sir Edward Heath, British Prime Minister from 1970 – 1974, bought the house in 1985 and lived there until his death. After his death, the house passed to a trust who have opened it up to the public.

Mompesson House: Owned by the National Trust, this 18th century, Grade I listed house is open to the public. It was built for Sir Thomas Mompesson, who was MP for Salisbury on three occasions at the end of the 17th century. Unfortunately closed on the day of our visit.

The Rifles Berkshire and Wiltshire Museum: Once a Medieval canonry, it was occupied by canons from 1227 until around the 15th century, when it passed to the Bishop of Salisbury and was used as a storehouse and administrative building, being known as ‘The Wardrobe’ from around 1543.

I am only sorry that my injury prevented me from further exploration as there is much more to see by continuing along the West Walk and around the River Avon and water meadows.